We're hoping to use the mercury mines at Almadén in our documentary-in-progress,

Flamenco: la tierra está viva (Flamenco: the Land Is Still Fertile). Because it seemed to use that the mines are a good representative of the centuries of discrimination and mistreatment of

gitanos in Spain, we wanted to film a scene there.

|

| Oh, why not. Me, getting ready to go down into the mine. |

Our original idea was to have singer and co-director Antonio de la Malena sing some flamenco

tientos from a CD called

Persecución, part of which refers to the mines. The album is sung by el Lebrijano with verses written by Felix Grande. On listening to the CD, however, I don´t much like the verses...not poetic enough for my taste.

|

| The second level of the mine. There are 32 levels, most of them flooded now. |

The next idea was for Malena to write some verses of

tientos, thinking of the mines and the

gitano prisoners. We´d film him inside the mines themselves, beside the tunnel called the

galeria de los gitanos. This would be reasonably complicated and expensive but if we got funding, well, why not?

But another problem has developed. For several centuries, the mines were run by a German banking company as a means for the Spanish crown to pay it back for some monstrous loans. The best work on what conditions were like in the mines is a secret report written by an agent of the Spanish king in which he interviewed both prisoners and the mine´s manager and prison supervisors.

|

| Until modern times, the mine shafts were lit with these oil lamps. |

This secret report was written in 1593 by Mateo Alemán, a lawyer and man later to become a novelist who was a great influence on Cervantes. Alemán, himself, served time in debtor´s prison and so was sympathetic to the prisoners and not to the German company managing the mines.

Luckily enough, I found a copy of his report in the library of the University of California at Berkeley. I´ve now read the entire thing plus an introduction written by a relatively contemporary Spanish poet.

Without going into too much detail, this secret report is helpful but problematic. In the first place, at the time it was written,

gitanos sent to the mines were sent for actual crimes. In later centuries, they were often sent simply for being

gitanos. It was against the law to be

gitano. That is more what we want to illustrate.

|

| Looking down the shaft where the water was brought up from lower levels. |

It is likely, however, that the conditions in the very late 16th century (1593) were not too different from the conditions in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, when

gitanos were sent to Almadén simply for being

gitanos. This would mean we could still make use of the secret report. But there is even another problem: lots more

gitanos were sent as prisoners to work (usually for life) on the Spanish galleons than were sent to the mines.

The galleons were sailing ships and as far as I know, there aren´t anyof those left. On the other hand, the people in charge of the mines would be delighted to have us film there. Bottom line is that we are now thinking of letting the narrator explain the galleon part, and still film Malena singing a

tientos in the mines - funding permitting.

NOTE: In addition to

gitanos, there were many white and even some Arab and black prisoners in the mines, along with slaves AND free miners. The worse thing about the mines, by the way, was the mercury poisoning. This is not to say that the prisoners and slaves were treated well; often, it was pretty brutal. But the mercury poisong...well, no fun.

|

| Water pump and bucket. |

AND A FINAL NOTE: The task that the prisoners and slaves were made to do that was hardest was pumping water out of the mine, which was done with a hand crank. The most dangerous job was sweeping ashes out of the processing shed.

__________________

Our next post will be related to our documentary,

Strong Roots, Bright Flowers: Arts of Mexican Immigrants and Chicanos. Keep up with our progress on the flamenco documentary and our other work by going to this

LINK.

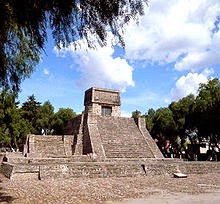

-Aztec%2Bball%2Bcourt.png)